This post was originally multiple posts over the academic year 2011-2012, to celebrate the LMU Centennial. These posts have been combined here for easier readability.

What were we reading in 1911?

The William H. Hannon Library celebrates the LMU Centennial through books (we are after all librarians!).

What were people reading during this time when William H. Taft was our president? When the US population was 93,863,000, there were 46 stars in our flag, the cost of a first-class stamp was only $0.02 and the U.S. was crossed by plane for the first time –and it only took 50 days!

Each month one of our librarians will look at a notable book published during 1911, and give you a glimpse of what people were reading while Loyola Marymount University was just getting started.

Our first contribution comes from Glenn Johnson-Grau, collection development librarian, who shares his perspective on this novel from a literary giant, Joseph Conrad.

Terrorism. Ideological extremism. Police surveillance. Political and social currents in a far off land that are alien and impenetrable to observers in the West. Joseph Conrad’s 1911 novel Under Western Eyes depicts the ripples of a violent act through society and individual lives. In the years after its publication it was seen as prescient concerning the start of World War I and the Russian Revolution; its continued relevance as an examination of the fallout from a fanatical act has been much noted in the post-9/11 era.

The novel came just past the midpoint in Conrad’s literary career, written after many of the works that now support his reputation as one of the great novelists in English and a precursor to literary modernism, but before he achieved commercial success. The son of Polish nationalists, Conrad fled his homeland for France to avoid conscription in the Russian army (Poland being ruled by the Russian Empire at the time). He joined first the French and then the British merchant navy; these travels took him to the locales depicted in his most famous works: South America in Nostromo, Malaysia in Lord Jim, and the Congo in Heart of Darkness. He retired as a ship’s captain in his late thirties for health reasons and to pursue a career as a writer; amazingly, English was his third language, after Polish and French.

Under Western Eyes is a political story but like its progenitor Crime and Punishment, it primarily focuses on the moral and psychological ramifications of a violent act. The story follows Razumov, a self-centered student who finds an acquaintance named Haldin in his apartment where Haldin confesses that he has just assassinated a government minister. Rasumov, inconvenienced by Haldin’s confession and by his political ardor, betrays Haldin and slowly becomes an agent for the Tsarist regime. Rasumov is sent as a secret agent to Geneva to infiltrate the revolutionary Russian expatriate community, who unknowingly embrace him as a hero. Rasumov’s guilt from his undeserved celebrity and the affection shown to him by Haldin’s sister Natalie send Rasumov’s life unraveling.

One of the most interesting facets of the novel is a framing device used by Conrad, where the narrator is an English teacher in Geneva recounting Rasumov’s story. This allows Conrad to tell the story of radical turmoil in the East from the perspective of an observer from the West, echoing Conrad’s own dual role as both a Pole and an English novelist incorporating topical events for an audience unaware of the perspective of the actors. In the years since 9/11, critics have noted the way that Conrad explores the psychology of extremism and the reactions that result from radicalism. As a twenty-first century reader, in addition to my enjoyment of a hundred year old psychologically complex political novel, considered one of Conrad’s greatest works, I was struck by Conrad’s point of the difficulty, perhaps the impossibility, for an outsider to truly understand the thinking and the cultural milieu behind far-away events.

— Glenn Johnson-Grau

Photograph of 1911 first editions courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, William H. Hannon Library

Our second review in the series comes from Dean of the Library Kristine Brancolini.

Decades before he became the acclaimed author of An American Tragedy, Theodore Dreiser wrote two controversial novels based on the lives of his older sisters, Emma and Mame. The first of these novels was Sister Carrie and the second was Jennie Gerhardt. Not one to shy away from sensational social issues, in Jennie Gerhardt Dreiser focuses on a young, middle class German-American woman who becomes pregnant out of wedlock by one man and then lives with another in the late 19th century. The publication of Sister Carrie in 1900 was all but buried by its publisher, who was scandalized by the content. Dreiser wrote a draft of Jennie Gerhardt in 1901 and 1902, acutely aware that, like Sister Carrie, it was likely to face publisher resistance due to the frank nature of its content. However, Dreiser suffered a nervous breakdown in late 1902 and he did not return to the manuscript until January 1911. He worked quickly to complete the novel, which was published in late 1911.

Jennie Gerhardt opens in 1880, when 18-year-old Jennie and her mother are forced to seek work in a posh Columbus, Ohio, hotel. Jennie is drawn into a world of wealth and influence, sex roles and class consciousness. Seduced by a U.S. senator more than 30 years her senior who promises to marry her, Jennie bears his child out of wedlock when the senator dies before they can marry. The focus of the novel soon shifts to Jennie’s relationship with a wealthy Cincinnati businessman, Lester Kane, whom she meets while serving as a lady’s maid in Cleveland. Lester is immediately taken with Jennie’s beauty and temperament and senses that she might be persuaded to enter into a sexual relationship with him. Although he is clearly attracted to her, he has no interest in marrying anyone, let alone a young woman so obviously beneath his social station. Jennie is loath to become involved in another extra-marital sexual relationship, but her father has been seriously injured in an accident and may never be able to work again. Lester offers considerable financial assistance if Jennie will come away with him. Her father would be furious if he knew the reality of the situation, but Jennie’s mother persuades her husband that Jennie and Lester are legally married. Jennie and her daughter Vesta eventually take up residence with Lester in Chicago; she begins calling herself Mrs. Kane. However, Lester’s family members in Cincinnati gradually learn of the deception and his father finds a way to persuade — or pressure — Lester to marry Jennie or separate from her.

Dreiser skillfully portrays Jennie’s dilemma and illuminates her strong character. Although she is not religious, in contrast to her Lutheran father, Jennie accepts that her behavior is wrong and that she is “bad.” It is clear that Dreiser believes in Jennie’s goodness. Jennie would like to be married, but the birth of her daughter has probably made that impossible for her. Strictly speaking Jennie can choose her course of action, but her family has few options. These were the years before health insurance and disability insurance. If the family breadwinner were sick and could not work, the family had no income until he recovered. If he could never work again, the older children had to quit school and support the younger ones by working menial jobs. Lester sees the situation and offers Jennie, who has fallen in love with him, a very attractive way out. Jennie is an extremely sympathetic character and although Lester is reprehensible in many ways, the reader wonders what would have become of the Gerhardt family without him.

Desperate for a bestseller, the manuscript of Jennie Gerhardt was heavily edited by Dreiser’s Harpers editor Ridley Hitchcock before its publication in 1911. More than 16,000 words were edited from Dreiser’s manuscript, removing any profanity, references to sex and much of his social and philosophical commentary. Oddly, Dreiser’s straightforward prose was rewritten to be more verbose and flowery. Jennie’s character was also altered, portraying her more blandly than originally conceived by Dreiser. The edition I read is the novel published in 1911, but in 1992 the University of Pennsylvania published the restored manuscript with historical commentary and a textual table showing each word change.

–Kristine Brancolini

Our third review in the series comes from Systems Librarian Meghan Weeks.

Ethan Frome is a tragic novel written by Edith Wharton, started in 1907 and first published in 1911. Wharton, whose maiden name was Edith Newbold Jones, was born in 1862 to a wealthy family. (Some say that the phrase “Keeping up with the Joneses” refers to Edith’s family.) Growing up in the United States and Europe, she was educated by private tutors. In New York in 1885, she married Edward Robbins Wharton, but divorced him in 1913. She wrote several novels, short stories, and poems, including The Age of Innocence, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1921.

Ethan Frome is a tragic novel written by Edith Wharton, started in 1907 and first published in 1911. Wharton, whose maiden name was Edith Newbold Jones, was born in 1862 to a wealthy family. (Some say that the phrase “Keeping up with the Joneses” refers to Edith’s family.) Growing up in the United States and Europe, she was educated by private tutors. In New York in 1885, she married Edward Robbins Wharton, but divorced him in 1913. She wrote several novels, short stories, and poems, including The Age of Innocence, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1921.

Ethan Frome is set in the village of Starkfield, Massachusetts. Although Starkfield is a fictitious place, the name aptly describes the setting, which is desloate and suffers from especially harsh winters. The first chapter is told from the viewpoint of a visitor who stays in Starkfield one winter while working nearby. This visitor, who is never named, occasionally encounters a curious man whom he describes as “the most striking figure in Starkfield, though he was but the ruin of a man.” This man is Ethan Frome. Ethan is very tall, but his right side is mangled, causing him to walk with a decided limp. The visitor is curious about Ethan and what happened to him, and asks around, getting bits and pieces of the story from the villagers about a “smash-up” that happened many years ago and which caused Ethan’s lameness. Then one week, the visitor has to hire Ethan to take him to and from work, but there is a blizzard and the visitor stays a night on Ethan’s farm. When he goes into Ethan’s house, he “[begins] to put together this vision of his story.”

The second chapter starts the “vision” which goes back more than twenty years before the “smash-up.” Ethan is a young man who was studying to be an engineer but had to come home to care for the farm after his father had an accident. His father dies and his mother becomes ill. His cousin, Zeena, comes to live with them and helps to care for his mother. Ethan’s mother passes away during one of those Starkfield winters, and out of desperation and gratitude Ethan asks Zeena to be his wife. Soon after their marriage, though, Zeena becomes sickly and her cousin Mattie comes to live with them as an unpaid servant. Mattie’s parents had died and left her with very little money, and since she is neither skilled nor educated enough to find work, she has nowhere to go. Ethan and Mattie develop a mutual attraction which does not go unnoticed by Zeena.

One day, Zeena announces that her illness is much worse, and she must go to one of the bigger towns to see a new doctor. Ethan is excited that he will be alone with Mattie and they have a nice dinner together at the farm, but the cat accidentally breaks one of Zeena’s favorite pickle dishes given to her by a relative. Ethan plans to glue it back together temporarily and hope that Zeena doesn’t notice it before he can replace it. However, Zeena comes back the next day and tells Ethan that the doctor says she needs a “hired girl” and that Mattie must go to make room for her. Zeena also finds the broken dish, which strengthens her decision that Mattie must go the following day. Ethan, furious and distraught, considers leaving with Mattie, but comes to the realization that he must stay because he doesn’t have the money to start a new life with Mattie. He also feels guilty because Zeena would have no one to care for her and no means to support herself.

Ethan, against Zeena’s wishes, decides to take Mattie to the train station himself. On the way there, they lament over their separation and stop at a hill where they had planned to go sledding before Zeena’s early return. The hill is a steep and curved slope with a big elm tree at the bottom. They decide to take the sled ride that they had planned before they part ways. Walking back up the hill, they embrace with a kiss and Mattie suggests that go down again, this time going straight into the elm tree so that they would “never have to leave each other any more.” Ethan agrees, and they go down the hill once more and right into that elm tree. Their wish to not leave each other comes true—but not in the way that either had envisioned. Ethan turns into the mangled man described in the first chapter, Mattie ends up paralyzed, and Zeena now has to take care of both of them. In the final chapter, the visitor describes when he first sees all three of them as he enters the Frome house on the night of the blizzard, and how twenty years of suffering in this tragic situation have sapped the life out of all of them.

Ethan Frome is considered by many to be Wharton’s most tragic novel and it varies from her other works in that it portrays simple people in a small New England village rather than aristocrats. A couple of themes that make this novel as interesting today as it was when it was published in 1911 are the struggle between personal happiness and a person’s sense of duty or responsibility and how a person’s environment, in this instance the landscape and poverty, can have a negative effect on his/her emotional well-being.

Our fourth review in the series comes from a guest reviewer, LMU Senior Vice President and Chief Academic Officer Joseph Hellige.

How Little We Mortals Know: Review of The Sea Fairies by L. Frank Baum (Chicago: Reilly and Britton, 1911)

“Nobody ever sawr a mermaid an’ lived to tell the tale.”

“Nobody ever sawr a mermaid an’ lived to tell the tale.”

So says retired Captain Bill Waddle to young Mayre (“Trot”) Griffiths to begin L. Frank Baum’s fantasy of life under the sea. Like most young girls, Trot is full of questions and, now that his seafaring days have been ended by an accident, the peg-legged Cap’n Bill is grateful to spend his days teaching her about life on the sea and regaling her with legends of the world beneath.

Trot is especially curious about those sea fairies known as mermaids and wishes with all her heart that she could meet one. Having heard her wish and wanting to correct the misinformation given by Cap’n Bill, the mermaids Merla and Clia transform Trot and Cap’n Bill into mermaid and merman, complete with scaled tails shimmering pink and green, respectively. The resulting tour through the depths of the deep blue sea is filled with sights, sounds, and adventures that rival those of Baum’s better-known “Oz” series.

The first time my family vacationed at the Hotel del Coronado with our then young daughters, I noticed the framed photographs of L. Frank Baum and the accompanying text about the frequent visits from his home in Hollywood for relaxing and writing. So began my interest in his work and the discovery of just how prolific he was. Shortly after, I picked up a copy of The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus (1902) and read from it nightly to my girls. It remains one of our favorites. It is with the same sense of delight that I discovered and read The Sea Fairies.

In this 1911 novel, Baum paints wondrous word pictures of life among the mermaids and their queen, Aquamarine, who introduces them to King Anko, an enormous, powerful, and patriarchal sea serpent who presides over his kingdom with beneficence. The role of chief villain is played by Zog the Magician, a hideous mixture of fish, animal, and human, who enlists sea devil assistants to capture the visitors and their mermaid escorts. The protagonists learn that sailors believed to have been drowned have actually been enslaved and held captive in Zog’s lair. Among these are Cap’n Bill’s brother, Cap’n Joe. True to the form of this genre, Zog is eventually defeated with King Anko’s help, his prisoners are released, Cap’n Joe is chosen to be their new king, and Trot and Cap’n Bill return to dry land.

As is true of Baum’s other work, The Sea Fairies mixes fanciful children’s fare with social commentary, wry political observations, and light-hearted wordplay that is meant more for us grownups. For example, at one point Trot is confused by King Anko’s account of struggling to untie a painful knot in his enormous tail. When she tells him that she does not understand him, the King thanks her, saying

“People who are always understood are very common. You are sure to respect those you can’t understand, for you feel that perhaps they know more than you do.”

Elsewhere, there are barnacles who love to sing meaningless ditties:

“Please go away and come some other day;

Goliath tussels

With Samson’s muscles

Yet the mussels never fight in Oyster Bay.”

And, snooty codfish, of whom Cap’n Bill says:

“I’ve heard tell of codfish aristocracy but I never knowed ‘zac’ly what it meant afore….but I ain’t sure they understand what they’re like when they’re salted an’ hung up in the pantry. Folks gener’ly gets stuck-up ‘cause they don’t know theirselves like other folks knows ‘em.”

More in Baum’s time than today, the term “codfish aristocracy” was used in reference to ostentatious displays of recently acquired wealth. The reference stems from the organization of New England colonist sailors into a “codfish aristocracy,” whose new-found wealth was acquired from the sea and who rose up against British tariffs on fishing. So important were these fish aristocrats that an effigy of the codfish still hangs in the chamber of the House of Representatives in the Massachusetts statehouse in Boston.

To a well-dressed, though somewhat greedy, octopus Trot shares that up on dry land they call the “Stannerd Oil Company” an octopus, prompting the following exchange:

“Stop, stop!” cried the monster in a pleading voice. “Do you mean to tell me that the earth people whom I have always respected compare me to the Stannerd Oil Company?”

“Yes,” said Trot positively.

“Oh, what a disgrace! What a cruel, direful, dreadful disgrace!” moaned the Octopus, drooping his head in shame, and Trot could see great tears falling down his cheeks.

At another point the protagonists happen on an excited school of mackerel in time to hear the fish proclaim that one of their group, Flippity, has just gone to glory. Turning to their mermaid escort, Merla, Trot asks:

“What does it mean? How did Flippity go to glory?”

“Why, he was caught by a hook and pulled out of the water into some boat,” Merla explained. “But these poor stupid creatures do not understand that, and when one of them is jerked out of the water and disappears, they have the idea he has gone to glory, which means to them some unknown but beautiful sea.”

Of humans who might also be said to have gone to their glory, the villainous sea monster Zog tells Trot and Cap’n Bill,

“The dying does not amount to much. It is the thinking about it that hurts you mortals most. I’ve watched many a shipwreck at sea, and the people would howl and scream for hours before the ship broke up. Their terror was very enjoyable [to me] But when the end came, they all drowned as peacefully as if they were going to sleep, so it didn’t amuse me at all.”

All grand adventures end eventually, and The Sea Fairies is no exception. Baum followed this novel with one sequel and then returned to the “Oz” series for which he had become famous years earlier. Neither Trot nor Cap’n Bill were forgotten, however, and both make appearances in some of the later “Oz” stories. As for their adventure in The Sea Fairies, that, too, was destined to end with them back on earth where they belonged. As Trot says,

“The land’s the best, Cap’n.”

“It is, mate, for livin’ on,” he answered.

“But I’m glad to have seen the mermaids,” she added…

“Well, so’m I, Trot,” he agreed. “But I wouldn’t ‘a’ believed any mortal could ever ‘a’ seen ‘em an’–“

Trot laughed merrily.

“An’ lived to tell the tale!” she cried, her eyes dancing with mischief. “Oh, Cap’n Bill, how little we mortals know!”

“True enough, mate,” he replied, “but we-re a-learnin’ something ev’ry day.”

Indeed!

Interesting Web Resources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L._Frank_Baum

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sea_Fairies

http://masstraveljournal.com/features/places/boston-cambridge/boston/massachusetts-fish-story

http://www.amazon.com/Sea-Fairies-Dover-Childrens-Classics/dp/0486401820

Our fifth review in the series comes from Head Cataloging Librarian Walter Walker.

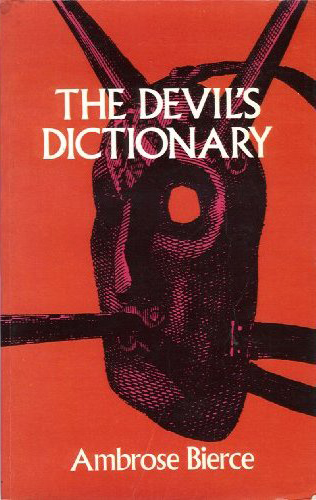

After several years of distinguished soldiering in the Civil War, the almost completely self-taught Ambrose Bierce became one of the most colorful figures in late 19th– and early 20th-century journalism in America. In San Francisco, where he spent most of his life, he was a newspaper editor and columnist, and delighted in exposing hypocrisy and stupidity in private and public life. Bierce was known in California as “the wickedest man in San Francisco” and in London as “Bitter Bierce”. His friend H.L. Mencken said “What delighted him most in this life was the spectacle of human cowardice and folly.” Ambrose brought his gift of satire and misanthropic attitude to writing a dictionary that was eventually entitled The Devil’s Dictionary and published in 1911.

After several years of distinguished soldiering in the Civil War, the almost completely self-taught Ambrose Bierce became one of the most colorful figures in late 19th– and early 20th-century journalism in America. In San Francisco, where he spent most of his life, he was a newspaper editor and columnist, and delighted in exposing hypocrisy and stupidity in private and public life. Bierce was known in California as “the wickedest man in San Francisco” and in London as “Bitter Bierce”. His friend H.L. Mencken said “What delighted him most in this life was the spectacle of human cowardice and folly.” Ambrose brought his gift of satire and misanthropic attitude to writing a dictionary that was eventually entitled The Devil’s Dictionary and published in 1911.

Bierce had used the title “The Devil’s Dictionary” for newspaper columns defining words, then published the definitions from A-L in The Cynic’s Word Book in 1906. He said “Here in the East, the Devil is a sacred personage (the Fourth Person of the Trinity as an Irishman might say) and his name must not be taken in vain.” He was forced to accept the original title because of his publisher’s prudishness concerning the word “devil”, but he later restored the preferred designation. The satirical definition was quite common in nineteenth-century literature, but Bierce’s handling of it transcends the ordinary in several respects. His savage denunciation of mankind, tempered only by verbal humor and mordant wit, gradually overwhelms all but the most cynical of readers.

Here are some examples of his definitions:

Absolute, adj. Independent, irresponsible. An absolute monarchy is one in which the sovereign does as he pleases so long as he pleases the assassins. Not many absolute monarchies are left, most of them having been replaced by limited monarchies, where the sovereign’s power for evil (and for good) is greatly curtailed, and by republics, which are governed by chance.

Absurdity, n. A statement or belief manifestly inconsistent with one’s own opinion.

Academe, n. An ancient school where morality and philosophy were taught.

Academy, n. (from academe). A modern school where football is taught.

Bore, n. A person who talks when you wish him to listen.

Peace, n. In international affairs, a period of cheating between two periods of fighting.

Positive, adj. Mistaken at the top of one’s voice.

Wall Street, n. A symbol of sin for every devil to rebuke. That Wall Street is a den of thieves is a belief that serves every unsuccessful thief in place of a hope in Heaven.

He often adds to the entries comical “scholarship” in prose or poetry written by such “expert commentators” as “Father Gassalasca Jape, S.J.” or “Phela Orm”. For example, the definition for Carmelite includes a poem attributed to “G.J.” about a drunk monk, Death, and a fat horse. Since “jape” is a trick or practical joke, the Jesuit priest Father Jape is probably a figment of Bierce’s imagination.

It is quite obvious that this book was written over a century ago when one sees the archaic attitudes toward minorities and women. He uses the n-word in the definition of African, and it is sometimes difficult to ascertain if his definitions are making fun of women or of misogynistic men. For example, Indiscretion is “The guilt of woman,” Ugliness is “The gift of the gods to certain women, entailing virtue without humility,” and Garter is “an elastic band intended to keep a woman from coming out of her stockings and desolating the country.” He also said “Ah, that we could fall into women’s arms without falling into their hands.” H. Greenbough Smith said that Bierce’s views of women were very strange.

As a young man he was involved with a woman in her seventies, and later broke off an engagement to a young woman because of jealousy. He then married the daughter of a wealthy mining engineer and had a few children, but refused to see his wife anymore after he saw an admiring letter to her from a male friend (he said “I never take part in any competition—not even for the favor of a woman”). Soon after that, one of his sons committed suicide at age 16 after killing a rival in a duel over a girl in Chico, California. Perhaps Bierce’s difficult relationships with women, petty jealousies, and family tragedies shaped his philosophy and word definitions in The Devil’s Dictionary.

Ambrose Bierce’s book was popular 100 years ago, and many of his aphorisms are still quoted and cited today. Derek Abbott recently created Wickedictionary as an updated, contemporary version of The Devil’s Dictionary. Yet by 1927, H.L. Mencken said that it was out-of-print and difficult to find. Perhaps this illustrates that what is popular today may be forgotten 15 years later.

What happened to Ambrose Bierce? In November 1913, at the age of seventy-one, he joined Pancho Villa’s army in Mexico. He was last heard from in a letter dated December 26, 1913, and is presumed to have died in battle soon after, with his body burned when corpses were incinerated to prevent the spread of typhus. He had earlier said that he would not return from Mexico, and that “nobody will find my bones.” After his dramatic disappearance in Mexico, his works sank into obscurity.

However, I found The Devil’s Dictionary to be quite an amusing read, and a book that you can just dip into serendipitously. A few more examples:

Love, n. A temporary insanity curable by marriage or by removal of the patient from the influences under which he incurred the disorder.

Saint, n. A dead sinner revised and edited.

Dictionary, n. A malevolent literary device for cramping the growth of a language and making it hard and inelastic. This dictionary, however, is a most useful work.

(Want to read this book? If LMU’s copy is checked out, here’s an e-book, and don’t forget LINK+!)

Interested in more? Find more books reviewed as part of this series here.